Antique Vizagapatam

Vizagapatam – Beauty in Black & White

Delicate and beautifully detailed, antique Vizagapatam work makes a subtle statement in today’s interiors, says Clive Stewart-Lockhart

Delicate and beautifully detailed, antique Vizagapatam work makes a subtle statement in today’s interiors, says Clive Stewart-Lockhart

England, high summer, 1817. A young lady, let’s call her Emma, sits on the terrace of her country house, working at her sampler with a group of friends. As she reaches for her elegant, beautifully etched ivory workbox, she can’t help but feel a certain one-upmanship over her more provincial friends with their plain mahogany boxes. Hers, made in Vizagapatam,

India, was a gift from her husband who is stationed there with the army and although she really does love it, her sense of smugness is soon punctured by a pang of pain. Too awful to admit even to her friends, she suspects her husband to be having an affair with a local woman.

Such was the fate of many women during the 18th and 19th centuries. As their husbands set off to make their fortunes in the colonies, they either went with them to suffer a life in strange surroundings in the heat and without the family and home comforts they relied upon; or they stayed behind, uncomfortable in the knowledge that their husbands were unlikely to be faithful. Antique Vizagapatam wares conjure all this history and I think it is this, coupled with the outstanding workmanship, and the fact that wealthy Indians are increasingly looking to buy back their heritage, that has seen prices rise dramatically over the last 20 years.

What exactly is Vizagapatam work? Vizagapatam work is the term used to describe pieces made by Indian craftsmen around the town of the same name on the Coromandel Coast of India (modern day Visakhapatnam in Andhra Pradesh) throughout the 18th century and up to the mid 19th century. Typically, it displays grey/ black decoration on creamy white ivory, although styles changed over the years.

When was its heyday?

The popularity of Vizagapatam work is intrinsically tied up with its location – the town was a principal trading port between Europe and east Asia – and the companies that took advantage of that location to establish vastly profitable trade routes: the Dutch East India Company and the Honorable East India Company (HEIC).

An English textile factory was established in the town in the late 1680s and the HEIC established a base there three years later. Fast forward 100 years and the whole region was under the control of the British. It is difficult today to understand the power and influence of the HEIC. In essence, it ruled vast swathes of the subcontinent, even raising its own army.

British control survived a French naval attack in 1804 and, with peace restored, Vizagapatam must have been a fascinating, bustling place, with HEIC and private ships passing on their way to and from Canton in China and returning to England with shawls of bright chintz and ivories from India. Following the Great Rebellion of 1857, the influence of the HEIC rapidly faded and, by the 1870s, was all but over. The market for Vizagapatam work was reduced to a trickle of lesser pieces.

What type of pieces were made?

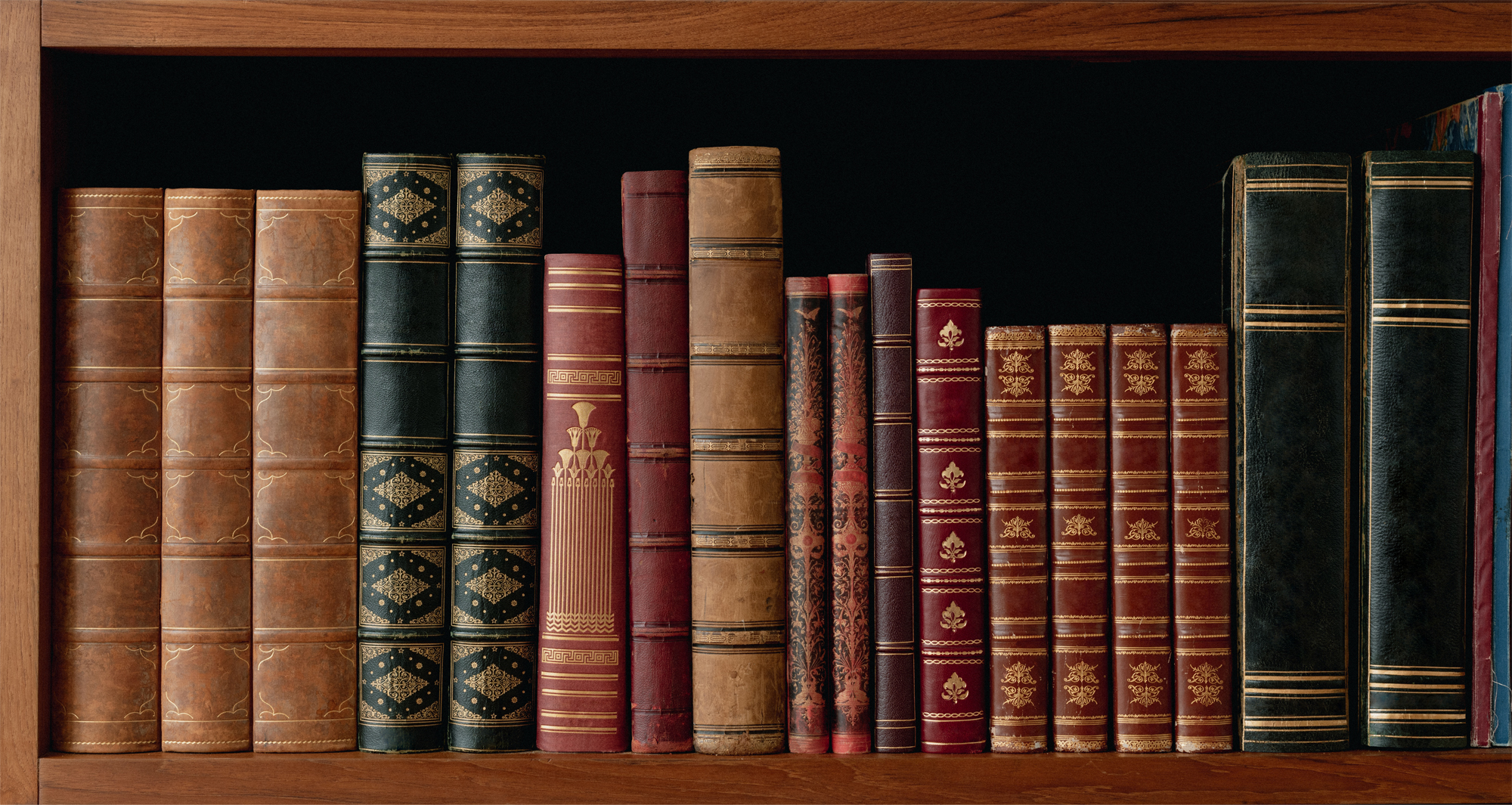

In the 17th and early 18th century, seat furniture and some spectacular pieces of case furniture were made. Most notable were bureau bookcases with flowers, birds and animals inlaid in ivory into rosewood and ebony, made for directors of the HEIC and governors of various parts of India. Indeed, as Major John Corneille wrote of Vizagapatam in the 1750s, ‘The place is remarkable for its inlay work, and justly, for they do it with the greatest perfection.’ Richard Benyon, the governor of Madras from 1735-44, brought back several wonderful things including a spectacular inlaid ivory bureau bookcase, still in the family seat at Englefield House, Berkshire, today.

In the 17th and early 18th century, seat furniture and some spectacular pieces of case furniture were made. Most notable were bureau bookcases with flowers, birds and animals inlaid in ivory into rosewood and ebony, made for directors of the HEIC and governors of various parts of India. Indeed, as Major John Corneille wrote of Vizagapatam in the 1750s, ‘The place is remarkable for its inlay work, and justly, for they do it with the greatest perfection.’ Richard Benyon, the governor of Madras from 1735-44, brought back several wonderful things including a spectacular inlaid ivory bureau bookcase, still in the family seat at Englefield House, Berkshire, today.

Who bought it?

As more British people moved to the area, whether as merchants, governors, civil servants, clerks for the HEIC (as Robert Clive, later Clive of India, initially did) or soldiers, the demand for western- style furniture spread. The very earliest Vizagapatam pieces from the late 1660s were chairs imitating the designs of English and Dutch furniture of the time but plentiful supplies of local materials such as ebony, sandalwood, teak, ivory and abalone shell added an exotic feel to these familiar shapes.

We know from contemporary inventories that local British residents had pieces in their houses and, as returning dignitaries such as Robert Clive and Warren Hastings (the first British governor-general of India from 1772-85) brought back large collections of Indian treasures and pieces such as tables, cabinets, chairs and boxes, demand for a piece of the east in well-to-do English houses burgeoned. A vibrant export trade grew up, with pieces generally becoming smaller and more portable (chess sets, workboxes and mirrors) as time went on.

By the end of the 18th century, the smaller size of the pieces produced dictated a change in style and technique. The use of ebony was fast dying out and pieces of ivory were no longer inlaid into solid timber. Instead, sheets of ivory were secured to the carcass, usually sandalwood, by small ivory pegs, before being engraved with designs. Initially, these designs were of trailing borders of foliage in a sparing neo-classical style with occasional pieces more extensively decorated. Cottage scenes often appear on workboxes, in imitation of designs found on Tunbridge ware. By the late 19th century, inlay and cheaper overlay strapwork (see Three of the Best) were in fashion once again.

We would like to thank Sue Herdman and Homes & Antiques magazine for permission to reprint this article.